On the Photographic Production of a German-origin Missionary Ethnographer

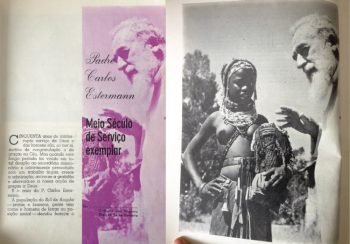

Charles Estermann (1889–1976) was a Spiritan missionary who spent about 50 years in Southern Angola (1926–1976). Born in German Alsace before the region became French, his ease with languages led him to Africa. Soon after arriving at Mupa, a hinterland mission in Southern Angola, Estermann started to develop a career as an ethnographer. He used manuscripts from previous missionaries to learn the local language, and took notes from his observations and of the answers he got from the people near the missions and at the visits he did to surrounding villages. In his missionary training, he had read many of the previous writings about the region, and was an avid reader all his life.

Publishing firstly in international scientific journals (1928), and later in the Portuguese ones, he became a prolific author, both as a social scientist and as a science communicator, in parallel with his missionary writing.

As Estermann’s photographic collection is currently lost, his photographic production can only be recovered by tracing his publishing trajectory. Although the later only reveals a partial understanding of his field photography practice, to follow it shows his recurrent use of photography and gives glimpses into his enduring relationship with photography.

1935, Boletim Geral das Colónias, "Notas Etnográficas do Distrito da Huíla" [PT]: 17 images, unassigned.

1935, Missões de Angola e Congo, “Conferência na Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa" [PT]: 3 images, unassigned.

1936, Bulletin de la Société Neuchateloise de Geographie, “Les Forgerons Kwanyama" [FR]: 4 photographs, unassigned [by Elmano Cunha e Costa].

1944, Portugal em África, “A festa de puberdade em algumas tribos de Angola meridional" [PT]: 5 photographs, unassigned (by C. Estermann).

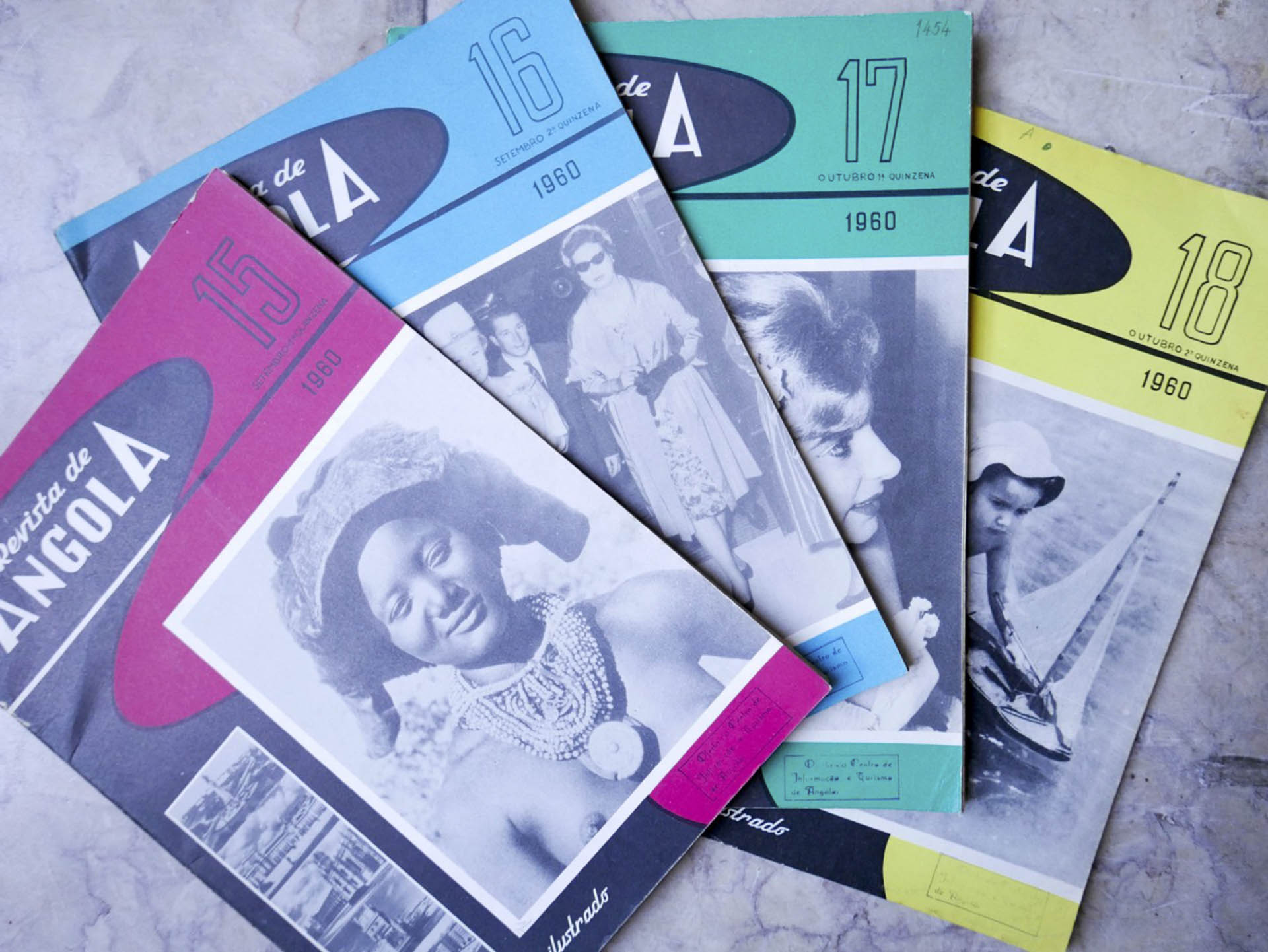

The covers of four different journals in which, during the early period of his missionary career in Angola, Estermann published articles with images. They cover the period between 1935 and 1944, and were based in Lisbon, Braga (both in Portugal) and Neuchâtel (Switzerland).

1946, Anthropos, "Quelques observations sur les Bochimans !Kung de l'Angola Méridionale" [FR]: 9 images.

1952, O Apostolado, “Is there a primitive communism among certain tribes in Angola" [PT]: 2 photographs.

1970, Álbum de Penteados, Adornos e Trabalhos das Muilas [captions: FR, PT, ENG]: 48 photographs.

The covers of an academic journal, of a missionary magazine and of a photo album where during his missionary career in Angola, Estermann published his own images. This alignment covers the period between 1946 and 1970, and the publication’s offices were based in Switzerland, in Luanda, and in Lisbon, respectively.

In early 1950s, being already an established and internationally recognized ethnographer, Estermann received the financial support by the Portuguese political regime of Estado Novo (1933-1974). The scholarship gave place to his major 3 volume monograph, for which he is currently better known. The volumes were published between 1956 and 1961. Before that, Estermann had received sporadic support from the colonial administration in Angola, namely through the Instituto de Investigação Cientifica de Angola. He also had significant relationships with the small scientific community established in Lubango over the long 50 year period of his stay. In the early 1970s, he wrote and displayed field photographs in publications related to the colonial administration, connected with topics such as settlement and tourism, responding to policies established in the late Portuguese colonial period.

1956, Ethnography of Southwest Angola, volume 1 [PT]: 99 photographs.

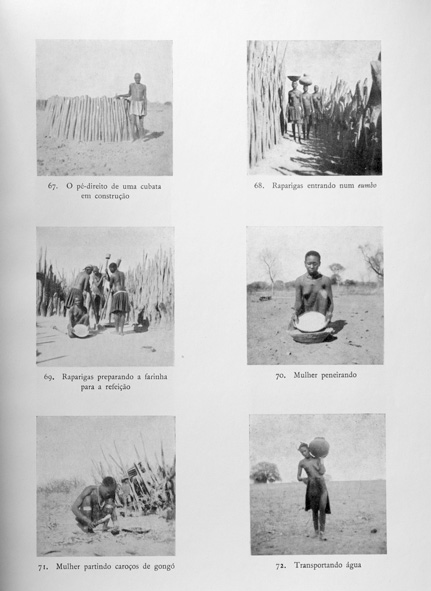

1956, Ethnography of Southwest Angola, volume 1 [PT]: page

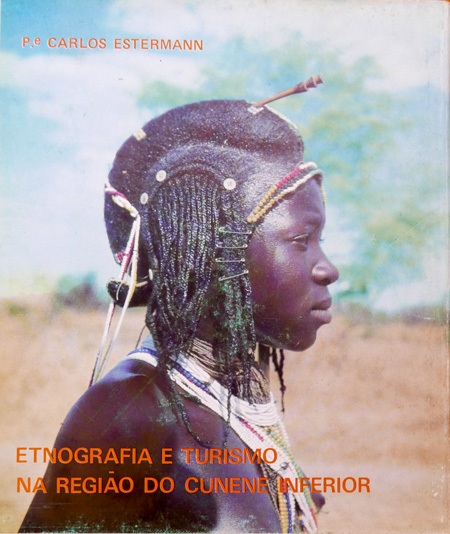

1972, Etnografia e Turismo na região do Cunene Inferior [captions: PT, ENG, FR, GER]: 40 photographs.

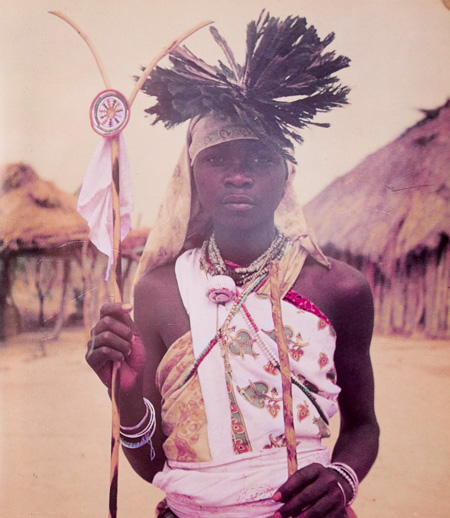

1972, Etnografia e Turismo na região do Cunene Inferior [captions: PT, ENG, FR, GER]: page [humbe boy, dressed like a girl and an added headdress].

The cover and an image page of two late Estermann’s publications, both through the Instituto de Investigações do Ultramar, Lisbon. The display of photographs of each contrast in size.

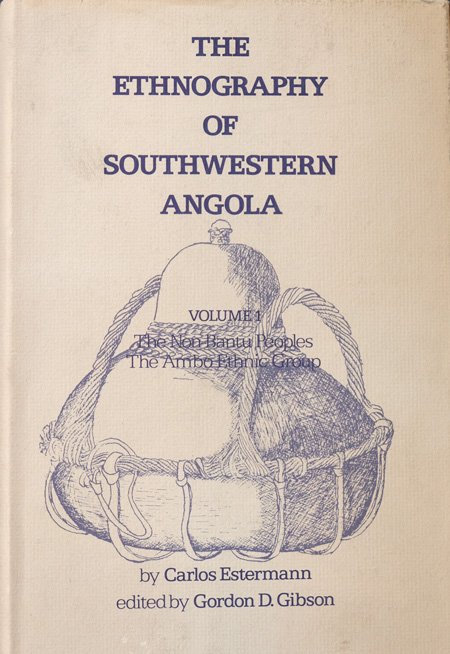

Shortly after his death, in 1976, international publishers edited English and French translations of his major three-volume monograph, The Ethnography of Southwestern Angola. Similarly to the Portuguese editions, the monograph includes hundreds of small-printed pictures such as a) portraits of people classified as members of specific ethnic groups, b) pictures of people in specific daily activities, such as fishing or making butter; c) photographs of members of those groups performing during various rites; d) photographs of people’s dwellings and of their material culture.

1957, Ethnography of Southwest Angola, second volume [PT]: 151 photographs.

The 1st volume of Ethnography of Southwestern Angola was published in English in 1976, the year Estermann passed away.

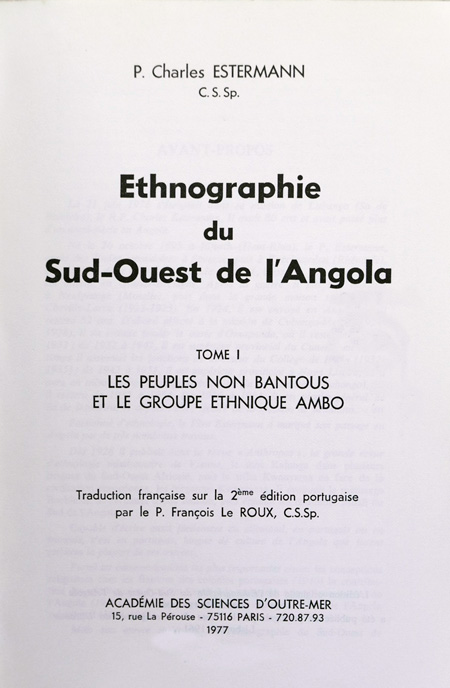

the French version of the first volume appeared in 1977.

The cover of three editions of Estermann’s magistral regional monograph, published in Portugal (1956-1961), in the USA (1976-81) and in France (1977).

1960, Revista de Angola, 15-18, images of hairstyles with short text

Some prints of Estermann’s photographs can be found scattered in a few institutional archives, such as at the Holy Spirit Congregation Archive, Portuguese Province (APPCMES), in Lisbon; at the Smithsonian Institute, in Washignton DC; and at the Huila Regional Museum, in Lubango, Angola.

For more information on the institutions that archive a few of Estermann’s photographs, see sources: archives and collections.

A graphical understanding of the recurrence of image in Estermann’s publication can be found in the section Visualise Mobilising Archives.